The Southern Surge: Understanding the Bright Spots in the Literacy Landscape

Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alabama offer a playbook for improving reading outcomes.

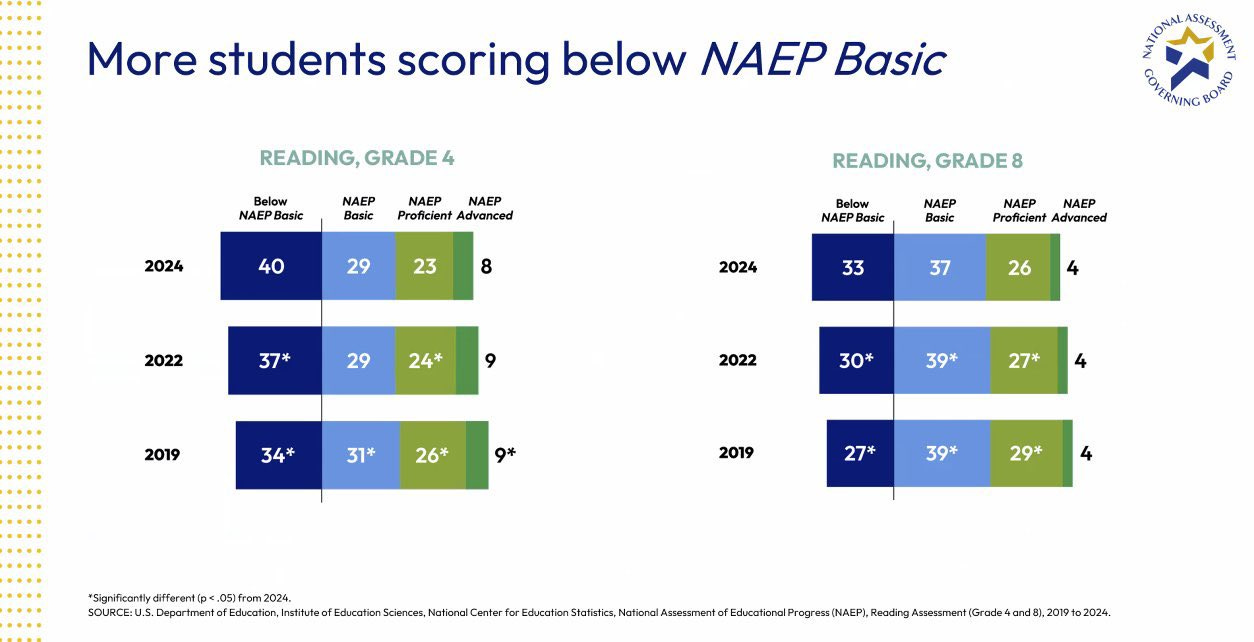

Our scores on the NAEP, a national reading exam of sorts, were grim. We saw the worst 4th grade reading outcomes in 20 years, as 40% of students scored below-basic. Reading scores hit historic low for eighth graders, with 33% below-basic.

Most conversation has focused on the culprits for the decline.

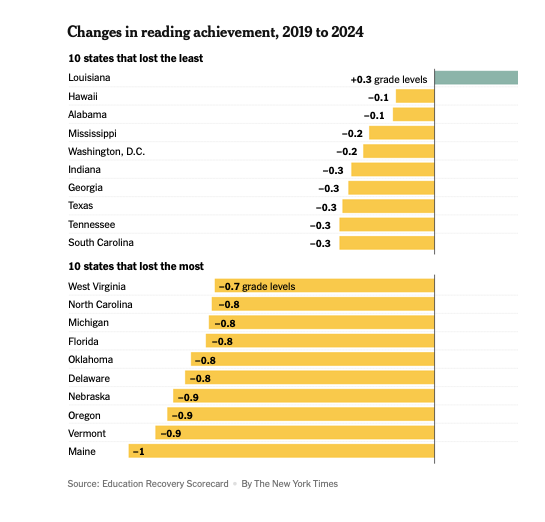

It’s just as important to dig into the bright spots in English Language Arts, because one cohort of states signals the way forward. I call them the Southern Surge states.

Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alabama stand out for reading growth, on both the NAEP and state testing. These four states weathered the pandemic better than most peers:

Three have shown notable growth in reading skills for underprivileged students; in fact, Mississippi and Louisiana are #1 and 2 in 4th grade reading when you adjust for demographics.

Collectively, they aren’t (yet) topping the nation for overall reading proficiency, although Mississippi, Tennessee, and Louisiana have moved into the top tier; they are tied for 14th in 4th grade reading proficiency. Instead, they compel attention because they are producing the clearest gains over the last 5 years, as other states backslide.

The Southern Surge shares a common playbook. All four states made a multilayered, sustained investment in both teacher training and curriculum improvement, alongside other reforms.

Together, these states send a clear signal that we can absolutely raise reading outcomes with the right investments, and they offer a blueprint to other states.

Let’s discuss the sources of the Southern Surge.

In Louisiana, a Curriculum Catalyst

“What happened in Louisiana??” was the question on everyone’s mind, given its convincing lead on fourth grade reading improvement since 2019.

In 2012, Louisiana embarked on ambitious efforts to improve the curriculum used statewide, charting an improvement path that was bolstered by 2021-23 Science of Reading literacy reforms.

A decade later, those investments are bearing fruit. Louisiana showed standout gains in NAEP fourth grade reading in both 2022 and 2024, making it the state with the greatest proficiency gains since 2019. Louisiana was one of the only two states to avoid a COVID dip in NAEP reading outcomes. Today, Louisiana has the second-best reading proficiency in the nation for low-income 4th graders.

What Louisiana did:

Louisiana’s story starts in the Common Core era, with a strong push to improve statewide curriculum to meet the new standards. In 2013, Louisiana began doing its own curriculum reviews and boosting the highest-quality options. Statewide contracts with those providers allowed districts to skip cumbersome procurement processes if they adopted the good stuff.

Louisiana also developed its own knowledge-building curriculum, Guidebooks, for grades 3-12. The freely-available materials, which were collaboratively-developed with teachers, were available in lower grades by 2016, and high school materials followed.

All of Louisiana’s early training efforts focused on implementation of high-quality materials. The Department of Education offered free professional learning workshops for specific curricula. In 2016-17, Louisiana launched a mentor program, complete with stipends, to train teachers as districtwide mentors in use of these curricula.

By 2016, Louisiana had launched a Professional Learning Vendor Guide, with a list of vetted options for curriculum-specific training. Grant opportunities were tied to using providers from that list.

In the initial phase (2013-16), Louisiana was still allowing districts to choose curriculum freely, alongside initiatives designed to “make the best curriculum choice the easy choice.” However, by 2016-17, the state was beginning to require districts to use high-quality programs; by that point, state leaders had enough buy-in to make that move, according to Rebecca Kockler, a Deputy Chief at the time.

Fresh legislation in 2021 and more in 2022 ushered in a wave of ‘science of reading’ reforms: By the 23-24 school year, all K-3 teachers were required to take Science of Reading training (minimum 55 hours) from one of four approved providers. New literacy screening was introduced in ‘22, with a requirement to notify parents of below-benchmark readers. Teacher certification was strengthened, three-cueing was banned, and a third grade retention law passed (going into effect this school year).

Still, the cornerstone has been the curriculum work, which continues to lead of Louisiana’s comprehensive literacy plan. Rod Naquin, who served as a teacher mentor before becoming a teacher trainer in Louisiana schools, emphasizes its importance: “We had a base of high-quality materials” on which all efforts built.

For additional reading, I’d suggest Robert Pondiscio’s 2017 column, Louisiana Threads the Needle on Curriculum Reform.

Tennessee, the New Template

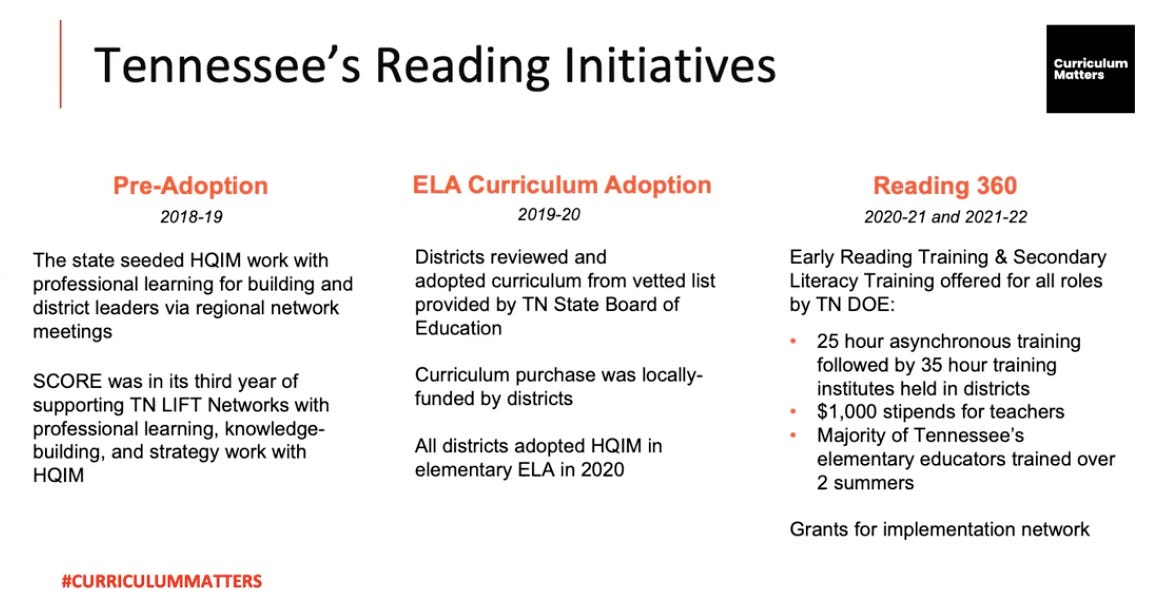

Tennessee is my favorite new model, because the Volunteer State has delivered swift gains. Its reading initiative kicked off six years ago, in 2018-19. Savvy Tennessee leaders borrowed the best of Louisiana’s and Mississippi’s models, adding their own innovations to produce the strongest template for states, in my opinion.

On the NAEP, Tennessee was 6th in the nation for the growth of its 4th graders and topped the country for growth of its 8th graders. Its state testing has shown steady gains: in 2021-22, its students were already showing ELA gains versus 2019 in nearly all grades, by 2022-23 they saw gains in all grades and subjects, and growth continued in most grades in 2023-24.

What Tennessee did:

Like Louisiana, Tennessee started with curriculum reform. Going into its 2020 state curriculum adoption, Tennessee worked to nurture local buy-in for curriculum improvement. The year before the adoption, they convened networks of district leaders and featured early adopter success stories for the best materials.

Tennessee’s 2019-20 ELA adoption offered a tightly-curated list of knowledge-building curricula. The state had a key tailwind: the ability to require schools to use a high-quality program in order to be eligible for state funding. Still, most districts in the state selected CKLA, Wit & Wisdom, or EL Education, the three best programs offered. Districts were encouraged to invest in deep teacher training on the curricula.

In 2020-21, as most districts were getting started with the new curricula, Tennessee kicked off its Reading360 initiative. The cornerstone was teacher training: Tennessee DOE developed its own training, more streamlined and focused than typical offerings, and trained nearly all of its elementary teachers over the course of two summers – the fastest pace of any state. Reading360 training was hand’s on; teachers worked with lessons from their actual curricula during in-person institutes. Thanks to this tangible approach, 97% of attendees gave the trainings high marks for utility.

Tennessee also released a free foundational skills curriculum in 2020, tapping literacy experts to enhance the CKLA materials. Many schools adopted it, thanks to its ease of use and affordability.

The broad investments paid off. Two years into its curriculum adoption, 96% of teachers reported that they primarily used the materials adopted by their districts, an unprecedented level of embrace.

Tennessee also kicked off a tutoring initiative in 2020 and passes a third grade retention law (which went into effect in 2023).

The comprehensiveness has paid off. Tennessee’s work has produced meaningful results in just a few years. If Tennessee stays the course, it will have a seismic story like Mississippi’s and Louisiana’s soon. I love the idea that the newer generation of pioneers can add velocity to this work by following the earlier leaders.

For more info, Robin McClellan told the Tennessee story in a webinar with fellow district leaders (excerpt below), and superintendent Scott Langford has written about its success factors.

The Mississippi Model

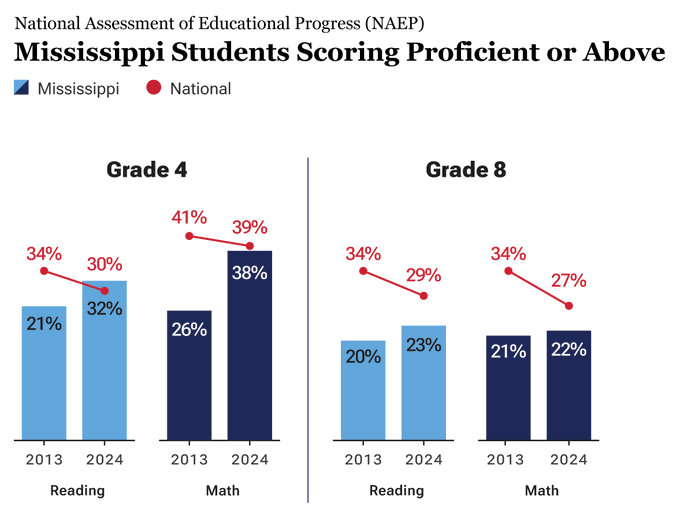

Missassippi’s success story needs the least introduction. Its results have inspired the nation and redefined what is possible, with more than a decade of sustained investment.

In 2003, Mississippi was 49th in the nation for 4th grade reading proficiency. Today, it ranks 9th. Mississippi is tied for third-highest reading proficiency for underprivileged children. Mississippi’s Black fourth graders were 43rd in the nation in 2003, and today they are third. In recent years, its 8th graders have begun to show reading gains, too. Mississippi’s growth in math proficiency has been even more striking, reminding us that the ability to read is a gating factor in math success.

What Mississippi Did:

Mississippi’s work has been covered pretty extensively, so I’ll keep this short, and focus on highlighting lesser-known details.

In 2013, the state passed a major bill, the Literacy-Based Promotion Act, ushering in a wave of investment in literacy. Many will tell you the work began a decade earlier, after Jim Barksdale invested $100M in a local reading institute, which pioneered in-school coaching efforts in high-need districts. Yet the 2013 legislation “brought the work to scale” statewide.

The Literacy-Based Promotion Act introduced new requirements for K-3 literacy screening, paired with parent notification for struggling readers. The state sent literacy coaches into the lowest-performing schools for 2-3 days a week, all year long. In low-performing schools, teachers were required to take intensive LETRS training on reading foundations. This training was optional for teachers in other districts, but when historically low-performing districts began outperforming wealthy districts in statewide screening, educators noticed, and teachers across Mississippi began to take advantage of subsidized LETRS training. In 2021, the state created special honors for schools with 80% of teachers trained.

The 2013 Act also introduced a third-grade retention requirement for children who weren’t reading successfully by the end of third grade. This was perhaps the most controversial aspect, though studies have found real benefits from this policy. Schools were required to provide intensive intervention and support for retained students, and also to assign retained students to a high-performing teacher the following year (a seldomly-discussed policy detail).

In the initial phase of statewide reform, Mississippi didn’t focus on curriculum. Leaders theorized that teacher training would inspire educators to select better materials. However, the state shifted gears in 2016, and began encouraging the use of high-quality curriculum. As a Mississippi state leader told me, “We recognized that while teachers were gaining valuable knowledge, they often lacked the necessary resources and materials for effective implementation.” By 2019, early adopters like Jackson Public Schools had upgraded curriculum, fueling growth. In 2021, the state released curriculum reviews, developed in partnership with EdReports, identifying six programs as high-quality (EL Education, CKLA, Wit & Wisdom, MyView, Into Reading, and Wonders). By 2024, 80% of districts had adopted one of these curricula in K-5, thanks to coaching by the state as well as grant funding for new materials and paired training.

Mississippi’s approach to teacher training also evolved through the years. Initially, LETRS training was its standard. Many advocates touted the role of LETRS in Mississippi’s success, to the point that the “Mississippi Miracle” became practically synonymous with LETRS. Few realize that in 2021, Mississippi moved to AIM ‘Pathways’ training, a more streamlined training (45 hours rather than 150 hours) that focuses less on theory and more on application.

Holly Korbey’s reporting details the ways Mississippi’s work has evolved through the years.

Mississippi has redefined what’s possible, inspiring a generation of states trying to replicate the model. You can find elements of its approach in every Southern Surge state, especially Alabama.

Alabama, the Ascendant

Alabama is the new kid on the growth block. Truth be told, we’re all still getting our heads around its story.

Alabama was one of only two states to show NAEP growth in 4th grade reading since 2019. In 2019, Alabama ranked 49th in for fourth-grade reading, and today it ranks 34th. Alabama was also 49th for low-income fourth-graders in 2019; today, it’s tied for 31st. Its state testing shows pronounced gains in reading.

What Alabama did:

Alabama’s Reading Initiative, kick-started by 2019 legislation, borrows a lot from the Mississippi Model: LETRS training and regular screening in K-3, literacy coaches in schools, and third grade retention. The retention mandates took effect in 2023-24, and I found it interesting and encouraging that less than 1% of third graders were, in fact, retained.

Alabama stands apart for its innovative summer reading camps. The lowest-performing students automatically receive invitations, and get 60 hours of intervention during the summer. The camps have been fostering growth; Sharon Lurye reported that Alabama “sent over 30,000 struggling readers to summer literacy camps last year. Half of those students tested at grade level by the end of the summer.”

Curriculum improvement has been a pillar of Alabama’s work. Beginning in 2022-23, all districts were required to have a comprehensive foundational skills program in place. Still, Alabama hasn’t yet made moves around core curriculum. I’m told that the state is just beginning to focus on knowledge-building curriculum, something to look for in the years to come.

Takeaways

The Southern Surge cements the case that money is not everything. All four states are in the bottom half for per-pupil spending, and Mississippi and Tennessee are in the bottom 10. However, all of these initiatives required significant investments, sustained over five- to fifteen-year periods. Professional development is a costly investment, so of course funding matters if you want to raise outcomes. The memo to states is to channel dollars towards specific and proven initiatives, not just district budgets.

The Southern Surge is also a fantastic reminder that poverty is not a learning disability. Mississippi and Louisiana have the highest childhood poverty rates in the nation, and Alabama and Tennessee are #6 and #11, respectively. Do not accept poverty as an excuse to let children’s education languish.

I don’t detail it extensively, but the states with reading initiatives are also some of the leading gainers in math, even when the states don’t seem to have significant math initiatives underway. Is this the natural byproduct of better reading, which we would expect to aid students in their work in math and other subject areas, or is there more to it? I hope we see more exploration.

The biggest takeaway is that investments must be multilayered and sustained. There were no silver bullets in Southern Surge states; rather, the intensiveness of their programs is light years ahead of most states chasing Science of Reading reform. Forty-five states passed reading legislation between 2019 and 2022, and while the reforms can mirror efforts in MS/LA/TN/AL, most states have surface level execution. Deep work is the way. So no, state leaders, you can’t just fund LETRS training for a pool of teachers, point districts to EdReports, and ban three-cueing and expect reading outcomes to change. They won’t.

Also, the state reform landscape is littered with cautionary tales. For example, Florida was a policy darling for a period of impressive reading gains, but recently, growth has tailed off. Alabama has been on a roller coaster: in the 2000’s, teacher training fueled reading gains, but the work wasn’t sustained and Alabama’s outcomes suffered. As its outcomes rebound, state leaders know they can’t take their feet off the gas.

Lastly, a word about politics. In the mean streets of social media, folks are bound to point out that these four states currently have Republican leadership, because it’s America in 2025, and we can’t help ourselves. I’d like to note a counterpoint: most of Louisiana’s work occurred under a Democrat, Governor Jon Bel Edwards (2016-24). I don’t deny that red states are generally showing more state leadership on literacy issues; personally, as a resident of New York – arguably the most laggard state in the country on literacy – it’s a point of chagrin. This is simply your daily reminder that the Science of Reading community is fundamentally bipartisan, and simple political rules can’t be applied.

In the Literacy Weeds

Closing with some in-the-weeds hot takes, for my educator friends:

There is a longstanding debate in the literacy space about the best order of operations: curriculum-first or training-first. This debate can feel like a red herring; all four Southern Surge states found both ingredients to be essential, and they lined up curriculum improvement and reading training in parallel or in rapid succession. That said, Tennessee and Louisiana offer the clear lesson that states (and districts) don’t need to hold off curriculum initiatives until all educators are trained; in fact, the opposite approach may have higher velocity.

On curriculum reviews: states with successful curriculum-led efforts, Louisiana and Tennessee, didn’t just default to EdReports for curriculum lists, they did local reviews to identify the very best options. I think that matters. Others may be coming to realize this: Mississippi worked with EdReports for its 2019-21 curriculum review effort, but close watchers note that under-fire EdReports is conspicuously absent from its review materials going into its next ELA adoption. If Mississippi can move from a mixed-quality curriculum list to a consistently strong set of options, I predict increased growth.

On teacher training: we shouldn’t miss the shift away from LETRS, the training that practically became synonymous with the “Misssissippi Miracle, to more streamlined, tangible training. LETRS training is 150 hours. Mississippi’s current AIM Pathways training is 45 hours. Tennesssee’s homegrown training was 60 hours. Louisiana requires 55 hours of training (from short list of providers). Asking teachers to take 150 hours of training is a LOT, and I have spoken with state leaders who hesitate about training mandates because they believe LETRS is the only option. We need to get the memo about alternatives to state and district leaders, alike.

And now, a word about fourth grade retention. All four states now have third grade retention laws, and Mississippi and Alabama led with this policy. I was pretty skittish about those laws a few years ago, but watching the Southern Surge closely, I’m changing my tune. I’ll try to write more about that, because it deserves more nuance than I’ll give it here.

At some point, as other states move to follow the Southern Surge playbook, we’ll probably see renewed efforts by Balanced Literacy educators to claim that the gains are a mirage caused by the retention policies, a myth we had to beat back about Mississippi’s story. Louisiana provides another good case study: its retention law is just going into effect this year. So, to borrow from James Carville: It’s the smart reforms, stupid, not some data anomaly from retention policies.

Lastly, we need a LOT more coverage of these success stories. Last January, I begged journalists to overcome their apparent hesitation about curriculum stories in The Grade. The Southern Surge stories lend weight to those pleas. Frankly, the Southern Surge helps explain why I am a curriculum maven in the first place.

Thank you to friends in all four of these states for your pioneering work, and for sharing your stories. Keep showing us all how it’s done.

"Mississippi’s approach to teacher training also evolved through the years. Initially, LETRS training was its standard. Many advocates touted the role of LETRS in Mississippi’s success, to the point that the “Mississippi Miracle” became practically synonymous with LETRS. Few realize that in 2021, Mississippi moved to AIM ‘Pathways’ training, a more streamlined training (45 hours rather than 150 hours) that focuses less on theory and more on application."

This is HUGELY important! I am concerned that we are both overtraining and overteaching, which brings with it all sorts of opportunity costs. "Bursting with Knowledge: Are We Overteaching Phonics?" (https://highfiveliteracy.com/2024/11/18/bursting-with-knowledge-are-we-overteaching-phonics/)

Thank you so much for doing this deep analysis Karen! The national

coverage has been anemic so you’re picking up the slack. When everything is failing, focusing on the bright spots is strategic.

By the way, what I’ve seen in research and practice work the best is integrating PD directly with curriculum. And we should build pedagogical content knowledge, such as how to teach blending - not mostly content knowledge, such as whether “fox” is 3 or 4 phonemes.